>>PERSPECTIVE II: ART ED TO TEACH DESIGN THINKING

PERSPECTIVE III: ART ED TO TEACH ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Important art, the kind worth spending years or decades learning to make, changes a target audience's attitudes or emotions. For instance, Picasso's paintings changed Gertrude Stein's feelings about herself. Buying his work made Stein feel important because she was a conspirator to Picasso's aesthetic revolution. She felt clever, ahead of the curve, privy to aesthetic sensibilities eluding her peers.

Triscuits packaging is important art too. Its designers trigger your associations to the mid-century Great Plains and the fresh ingredients you reflexively link to that setting. Design is always human-centered, always focused on flipping switches in a viewer's mind.

Seth Godin in Linchpin says school should do only two things:

(1) Teach students to solve interesting problems, and (2) teach students to lead.

A curriculum built around Design Thinking does both. Students solvea string of open ended problems.

- Suppose your Public Speaking Confidence Workshop wants to build a system that would make high school students less anxious when they present to the class.

- Suppose Crayola wants to launch a line of products for 11-14yo girls who used Crayola's products at a younger age. What needs, wants, or wounds do 11-14yo girls have? Invent a product to solve one of these problems for this market.

- Suppose Tobii wants to market passive eye-tracing technology to console gamers. What could eye-tracking do for gamers?

- How could Interbrand demonstrate ROI (return on investment) for the extravagant interiors they design and build for fashion/food retailers?

- SeaWorld just pledged to stop breeding orcas. The Shamu act is gone. Now that sea animal shows are off the table, how should SeaWorld rebrand themselves so they're not just an inferior Six Flags?

- How could farmland produce more nutrition per km²?

- How can Michele Obama's Let's Move campaign create an incentive system to get people off processed foods, turning them instead to fresh produce?

Look at the first example problem: Devise a system to make students in class less anxious when public speaking.

- EMPATHIZE: Students view presenters and their behavior in the context of their lives. They might even observe a round of classmates presentations. Some of the most useful realizations come from noticing a disconnect between what someone says and does.

- DEFINE: Student groups presented with this problem would first define (a) the target audience, (b) the design constraints, like how much time and money per presenter can be allotted, and (c) how they will identify that their subjects are less anxious. In this example, students report they want a majority of grade-10-to-12 art students to report, during a post-public-speaking interview, that they felt less anxious than they otherwise would.

- IDEATE: Student groups (preferably 6-8 students) brainstorm solutions. They discuss, write, sketch, and "bodystorm." Stanford d-School describes bodystorming, where students physically role-play as their user to anticipate solutions. Students vote on which 2 or 3 plausible solutions they'll prototype. In this example, they push two solutions on to the next step: (a) playing energetic music like Eye of the Tiger each time a student struts to the front of the class to present; (b) allowing a student to sit at a table in front of the class rather than stand at the front of the class.

- PROTOTYPE: Student groups build MVPs (minimum viable products) of 2-3 plausible solutions. They design an experiment to test their solutions' feasibility and effectiveness at bringing about the result described in DEFINE.

- TEST: Student groups test their prototypes on real subjects. If they have enough subjects, they might change a few variables in their prototype, which will allow them to A/B Test. In this example, students test theme music with no applause (getting the presenting student into the zone) against theme music with applause from the class (creating energy, enthusiasm, and support for the presenter).

- ITERATE: Student groups recalibrate or rebuild their prototypes based on feedback (in this example, exit interviews).

The entrepreneur Parker Thomas tells a story to show the extent to which design thinking permeates our routine behaviors:

The problem I was solving last night was not really how to make dinner; instead it was, “how can I make a nutritious and tasty meal in 30 minutes that my kids will like?”. As a devoted father and resident cook, I’ve conducted 10 years of research and hundreds of experiments to create a mental list of what my children will eat. When I made dinner last night, I checked my mental list against what I had in my fridge (design constraints), brainstormed a bunch of ideas (in my head, sorry no whiteboard in the kitchen) and picked a meal to prototype. I made the prototype and they ate it. Happy kids, happy dad. So my test was successful. And, while this may have all happened in the space of less than an hour at home, making dinner last night also hit every step of the Design Thinking process.Design Thinking is project-based-learning done right.

On the other hand, PBL done improperly leaves students in the shallow end of the pool where guesses aren't tested, like a chef who prepares a meal but won't taste it (and won't let anyone else taste it). And students lingering too long in the shallow end cultivate undue confidence in guessing how their art will affect target audiences. Or, they get in the habit of not even choosing a target audience! This is a "spray-and-pray" approach to art making. Students churn out content and pray their work will please the teacher or peers. Some learning certainly happens in the shallow end (for instance, students practice technical drawing, mixing color, and composing shapes in a pleasing way). But the really good stuff lives in the deep end.

A recent study exposed an epidemic of grad students publishing research with their experimental evidence falsified to support their hypotheses. Maybe secondary schools could buck this trend by pushing more students into the deep end. Teachers could train students to research for the sake of locating new insights, not proving their own guesses right. They could train students to feel safe when letting go of ineffective solutions, especially those that took effort to develop. A work of art is just one iteration. Take a breath, reflect, and go again.

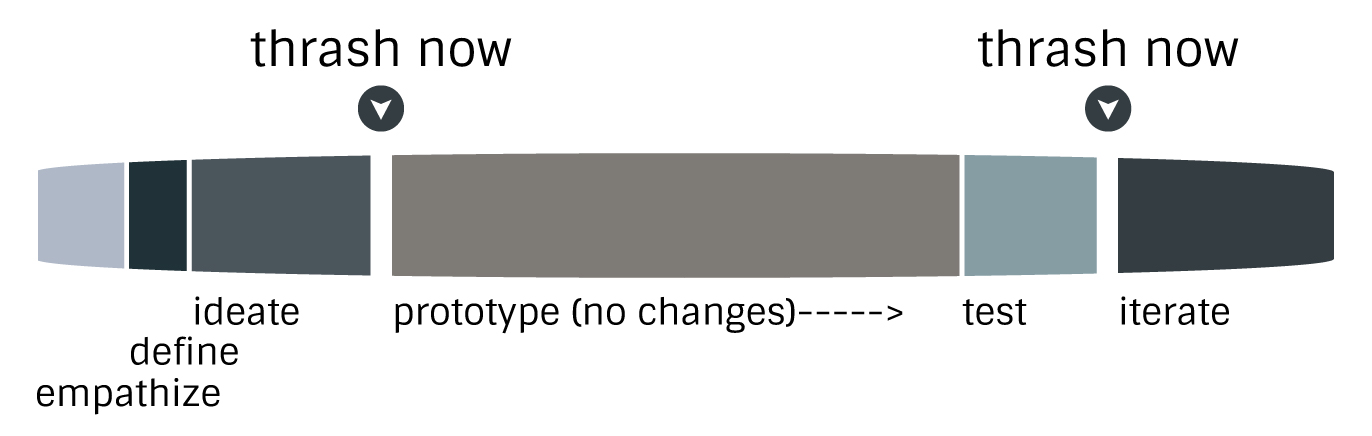

Another teachable habit is early thrashing on group projects. In Linchpin, Seth Godin says this about thrashing:

Any project worth doing involves invention, inspiration, and at least a little bit of making stuff up. Traditionally, we start with an inkling, adding more and more detail as we approach the ship date. And the closer we get to shipping, the more thrashing occurs. Thrashing is the apparently productive brainstorming and tweaking we do for a project as it develops. Thrashing might mean changing the user interface or rewriting an introductory paragraph. Sometimes thrashing is merely a tweak; other times it involves major surgery.Thus, early thrashing is a great habit for Design Thinking to instill in students. Students working in groups open the window wide to input at a project's start. Every group member brainstorms, shares and floats concerns early. After that, everyone commits to the group's collective mission. This process teaches students to elegantly voice suggestions or concerns about their group's trajectory. A teacher might even allot class time to practice giving feedback in a non-threatening manner. What an opportunity to teach a skill universally essential to career success!

Thrashing is essential. The question is: when to thrash?

In the typical amateur project, all the thrashing is near the end. The closer we get to shipping, the more people get involved, the more meetings we have [...] The point of getting everyone involved early is simple: thrash late and you won't ship. Thrash late and you introduce bugs. Professional creators thrash early. The closer the project gets to completion, the fewer people see it and the fewer changes are permitted.

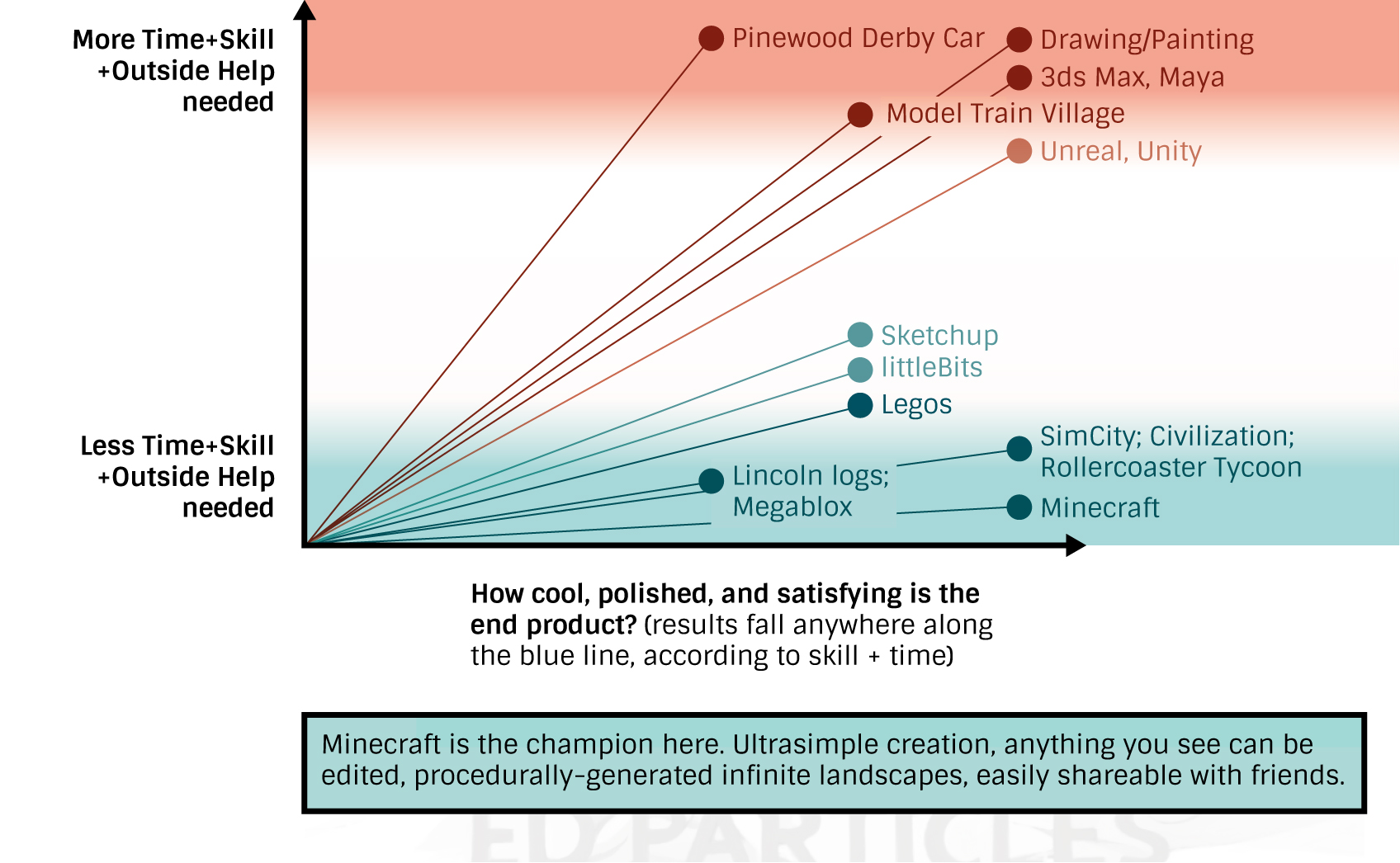

Each teacher should bring his or her areas of expertise into lesson creation. My background is packaging design, marketing, and retail design, so I might favor these areas. Another teacher might lean into photojournalism or environmental engineering. Keep in mind that the most efficient presentation gets students to the finish line most quickly. An infographic made with Canva will suffice, and no need to cut paper or mix acrylics.

I recommend that all Design Thinking instructors brush up on best practices for designing experiments, because students need help. They've almost certainly never designed experiments before. Statistical analyses like ANOVA are miles beyond the scope of what students must understand. Instead, I might help students devise a primitive A/B test, or a survey that students in period 3 could give to those in period 5. The validity of the A/B test or survey results is not important. What's important is that students identify a specific, testable outcome they want to bring about. They also have more incentive to make the deadline if peers will evaluate their work.

I've proposed that Design Thinking is PBL at its best, teaching students (1) to articulate and prioritize precise, testable outcomes, (2) to empathize with other people's needs, wants, and wounds, (3) to iterate towards solving a problem, (4) to work with a group of designers, blazing new trails.

Resources:

Design Thinking Toolkit by IDEO - free guide for teachers

This is Broken by Seth Godin - Video

Creating Worlds Through Design Thinking by Feng Zhu - Video

Change by Design by IDEO's CEO - book of Design Thinking best practices and real-life examples

The Bootcamp Bootleg by Stanford d-School - free guide for teachers

Running Lean by Ash Maurya - the best guide for students who intend to actually bring their solutions to market, this guide also helps students frame experiments for maximum learning per unit time

No comments:

Post a Comment